On April 7, 2013 Jose Fernandez made his MLB debut. The Marlins weren’t supposed to be very good, but they called up their top prospect anyway. Fernandez had only made 27 appearances in the minor leagues before his big league call-up. In total he threw just 138 innings in the Marlins’ system, but the team took the plunge and brought him up in response to injuries to a few of its starters.

The reaction was generally shock (calling up an A-ball pitcher for Opening Day isn’t exactly common, after all) followed by an attempt to rationalize the Marlins’ move. The team was decried for eating up some of Fernandez’s team control in what was likely to be a non-competitive season.

Fernandez dominated in his first start, a precursor to what would be a historic age-20 season. Unfortunately, he did this for a team that lost 100 games and finished in the cellar of the NL East.

The following season Fernandez got just over 50 innings in before his elbow gave out and Tommy John surgery claimed yet another victim. As Fernandez underwent surgery and rehabilitation, his service-time clock ticked. Valuable production was lost and the young pitcher’s not insignificant MLB salary still hit the Marlins’ bottom line.

***

Every team must go through a similar call-up calculus when deciding timelines for their top pitching prospects’ debuts. They must weigh a variety of factors like service time and the prospect’s development path to determine the right time to make a call up. What exactly are those factors?

Expected Performance

The decision to bring up a pitching prospect is rooted in the club’s expectation of his performance. Will he be better than the alternatives? Is he going to help maximize the likelihood of winning the games he starts?

The team often must decide between calling up their prospect and trying to use a swing-man or a journeyman sitting at Triple-A. For teams in contention, the reality that a prospect might give them a better chance to win than a swing-man makes calling that player up a tantalizing proposition. For teams no longer in the running for the playoffs, though, it’s easier to ignore expected performance in favor of longer-term goals. That means that in the end, even performance is just one piece of a much larger puzzle.

Options

If a player is added to the 25-man roster and then subsequently sent back to the minors, one of his three options years is triggered. That said, top pitching prospects are ideally not being shuttled between the majors and the minors. Assuming that’s the case, burning options is less of a factor because it’s likely that the pitcher will be up in the big leagues to stay after his first or second season.

Opportunity

A call-up requires an opportunity to get the player onto the 25-man roster and into the rotation or bullpen. It might be injury, as it was in the case of Fernandez. It might be the trade of veterans who open up a spot, as for Anthony Ranaudo last season. Maybe the team believes so much in a young pitcher that he makes his MLB debut because the club simply didn’t sign a veteran in the offseason to fill out its rotation. There are hundreds of scenarios that could lead to the call-up of a pitching prospect.

Opportunity isn’t necessarily a requirement for calling up a pitcher, but it is often a major factor in the decision. After all, a team typically needs to believe that the expected performance from the prospect in question will be better than the other options available to them, as we discussed before. In a way, that’s the most basic form of opportunity.

Prospect Readiness

This is the most fundamental component of player development, the goal of which is to train and improve the skill of players in order to maximize their talent. This is different from expected performance because prospect readiness concerns itself with the long-term ramifications of calling a player up. Does he still have things to work on in the minors? Is he dominating lesser competition and stagnating?

This is where the decision isn’t to be taken lightly. Calling a young pitcher up too early could ruin him for good. More often than not the result isn’t quite that doom-and-gloom, but there is a real chance of stunting the growth of a prospect because of overly aggressive promotion.

I asked BP’s Doug Thorburn for some thoughts on rushing pitching prospects and the potential downfalls of doing so:

For me, it’s all about pitch development, mechanics, and conditioning to endure a 162-game workload. If a guy is ready then he’s ready, whether he’s climbed the ladder one rung at a time or if he was good to go when drafted (e.g., Prior or Strasburg). It’s my contention that pitchers are babied in the minors these days, and the low pitch counts and pitch-type restrictions can get in the way of a pitcher’s specific development track.

So if a guy is called up before he’s ready – in terms of pitch development, mechanics, physical condition/stamina, or even mental/emotional preparedness – then a team could very well be robbing themselves of that player’s ceiling of performance. They only have 6 years of control, and if I’m a ballclub then I want the best 6 years, not the next 6 years. But if he’s advanced beyond his peers and his stuff/stamina/delivery are ready for the majors, then I could care less about the standard development curve or service time considerations. Why waste bullets in the minors that could be used effectively in the majors? (the key word being “effectively”).

I bolded two lines that really nail the development component of this debate for teams. Calling up a player too soon could lead to unfulfilled potential, but keeping a player in the minors too long might result in them wasting some of their best seasons in minor league stadiums.

Some teams have reputations for rushing pitchers, while others are notoriously slow to bring guys along. The Rays often take a slow, methodical approach, for example, while teams like the Orioles have reputations for moving guys more quickly. That said, regime changes can throw a serious wrench into these reputations.

Financial Ramifications

The major league minimum in 2015 is $507,500. That is, of course, the least worrisome financial factor for teams to consider. “Super Two” status is often cited, but rarely understood. Its impact on decision-making is immense. A practical example is worth exploring here, though we should note that it’s difficult to make meaningful comparisons because results, minimum salaries, and financial situations change over time. That said:

|

|

||

|

Debut |

5/12/2006 |

8/11/2006 |

|

Team Control Seasons |

6 |

7 |

|

ERA* |

3.39 |

3.84 |

|

IP* |

1,161 1/3 |

1,027 |

|

Total Salary* |

$36,775,000 |

$30,642,900 |

* Includes only the player’s pre–free agency seasons.

This isn’t a perfect comparison—Hamels was better than Garza by nearly half a run over the beginning of their careers—but it’s close enough to see the impact that being a Super Two can have. That’s not to mention that Hamels signed a multi-year deal during his arbitration seasons, so his earning power may have been somewhat stunted by his desire for more security.

Even if the effect is half of the difference illustrated above, that’s still 10 percent of what Garza made during his first seven seasons as a pro. That amount of money would have bought six minimum-salary players, a pretty good relief pitcher, or a utility man.

The impact of those extra costs can result in teams holding back players until after the Super Two deadline. So while pitchers like Garza may have been talented enough to come up when Hamels did, the fact that delaying his debut by a few months was certainly something important for the front office at the time to consider.

Team Control Time Frame

Team control is a significant portion of the calculus. We all know this by now as a result of the Kris Bryant dance, which BP’s own Craig Goldstein broke down in fine fashion. To quote Goldstein:

According to MLB rules, players become eligible for free agency—that is, free to field competitive bids for their services, sign with any team that wants them and (presumably) cash in on their true market value—after six full years of major league play. Those years are measured in “service time,” with one year being equal to 172 days out of the approximately 183 days on the MLB season calendar.

Because the gap between total days on the MLB calendar and a full year of service time is between 10 and 15 days, teams that hold down a prospect for the first 10 to 15 games of the big league season generally gain another year of control over that player, who will end their sixth season in the majors with something like five years and 160 days of service time. For the Cubs, sacrificing a few weeks of Bryant now will allow the franchise to own his rights through the 2021 season instead of 2020, which could give the team an additional season of superstar production at third base.

This is, by virtue of the rulebook, a no-brainer for teams. Simply keeping a player in the minors for just over two weeks results in an extra season of team control over the player. Because team control is kind of important to the team, this consideration often drives a part of the call-up decision for any given player.

Likelihood of Injury

This factor is, in many ways, the crux of this article. Jon Roegele has chronicled the “Tommy John epidemic” and the increasing frequency with which players are undergoing major elbow surgery. It’s gotten so bad that BP’s Effectively Wild podcast had a draft solely focused on avoiding pitchers who will need to have their UCL replaced in the next year.

The threat of Tommy John surgery, or another serious arm injury, seems always to be lingering over the head of pitchers. This has led fans and analysts, like Thorburn above, to advocate that pitchers not “waste bullets” in the minors if they’re ready for MLB. Should this knowledge—that pitchers are seemingly always on the brink of sustaining a major arm injury—cause teams to rush near-ready prospects to the show? Probably not, though there seems to be some appetite for that among followers of the game.

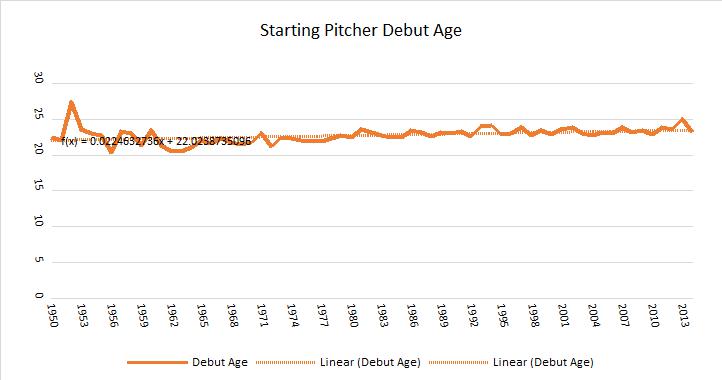

As it stands, it does not appear that teams are heeding these calls. The stats team here at BP pulled the average debut age for every pitcher who started at least 75 percent of his games in the first three years after his debut (to weed out late-bloomers who were bullpen-bound). I suspected that the debut age was getting younger, but you can clearly see that it has only increased since 1950:

Back in 1950 the average debut age was 22 years old, and it has increased about a year and a half over the last 65 seasons. While this is by no means a thorough analysis of whether teams are rushing prospects, it at least suggests that teams have rejected the idea of bringing players up earlier to get innings out of them before they hurt their arms. Indeed, if teams are taking development slower than ever before, that would seem to fit with the narrative around pitch- and innings-counts.

***

The Mets are an ideal case study for understanding this phenomenon in the field. The Mets were blessed with two excellent pitching prospects who came into this season on the cusp of the big league roster: Noah Syndergaard and Steven Matz. Both have excellent stuff, and both have track records of dominating the competition in the high minors. A rotation full of capable pitchers, though, meant both pitchers would start their seasons in Triple-A.

Eventually Syndergaard would get the call, and the club moved to a six-man rotation for some time to accommodate its pitching abundance. A few turns through the rotation and Syndergaard proved he belonged, seemingly for good. This has led to the recent development of the team reverting back to a normal five-man rotation, with Dillon Gee the odd hurler out.

Some claim that Matz hasn’t gotten the call because the club is worried about his Super Two status. Dave Cameron explains why that doesn’t pass the sniff test, though. Others claim, in light of a recent Gee quote about wasting bullets in the minors, that it is in fact Matz wasting precious bullets in the minors. The reality is that Matz simply doesn’t have the opportunity at present. The Mets have three young and talented pitchers in their rotation (Matt Harvey, Jacob deGrom, and Syndergaard) along with two pricey veterans (Bartolo Colon and Jon Niese). That doesn’t even include Gee, who is toiling away in the bullpen. The club seems to be attempting to address this logjam by moving an arm, but even that on its own wouldn’t open up a rotation spot.

If you want to know what’s really keeping Matz in Triple-A, you need look no further than the Mets’ depth chart. He’s obviously ready for MLB, we’re past the Super Two window, and the Mets will have him for that extra season. He’s likely to be a better option than Gee or Niese at this point, and he’s not lowering his injury likelihood by pitching every fifth day in the minors. The only roadblock to Matz’s debut is opportunity, one of the biggest factors in the prospect call-up calculus.

Thank you for reading

This is a free article. If you enjoyed it, consider subscribing to Baseball Prospectus. Subscriptions support ongoing public baseball research and analysis in an increasingly proprietary environment.

Subscribe now