BP Comment Quick Links

| |

February 19, 2009 Attack of the Finesse PitchersStrategery and Arms Control

"Hitting is timing. Pitching is upsetting timing."-Warren Spahn Prior to his July 10 meeting with the Phillies, Albert Pujols was sporting a gaudy .346/.467/.613 line with just 28 strikeouts in 334 plate appearances. The season's eventual MVP had been giving opposing pitchers fits, and it seemed unlikely that a pitcher with a 4.50 defense-neutral ERA and an average game score of 49 could do anything to change that. The Phillies, however, were counting on a starting pitcher with just those numbers in one Jamie Moyer, who was preparing to engage in another prototypical David vs. Goliath showdown with the game's best hitter, an imposing and muscle-bound 230-pounder standing no more than 60'6" away from a scrawny 46-year-old lefty with a fastball slower than Joe Sheehan's. Yet somehow, someway, six pitches into that fourth inning, Pujols would sullenly trot back to the visitor's dugout as a strikeout victim. How did Moyer and his 80 mph heater do it? For that matter, how can any pitcher like this, without a put-away pitch, who relies on acumen as opposed to "stuff," compete consistently in an environment in which they all too often appear overmatched? Granted, Pujols had singled off of Moyer in the at-bat preceding the strikeout, but Moyer's ability to adjust and miss the bat of the best hitter in the league speaks volumes. By definition, finesse pitchers walk and strike out less than 24 percent of their batters faced, a cap that makes sense given their pitch-to-contact mentality and penchant for limiting free passes. What differentiates these pitchers from the rest? Their method, which involves not only having less oomph on the fastball and placing more emphasis on movement, but also a lesser overall reliance on the fastball, must have some specific quantifications. To find out, I began by extracting the 2008 season lines of all major league pitchers from Retrosheet, calculating their walk and strikeout percentages, and summing the two. Next, each pitcher was coded as a finesse, neutral, or power pitcher based on the results. I repeated the same process for hitters, classifying each one as either a contact, average, or power hitter based on their slugging percentages. The results were then linked to my Pitch-f/x database, so that every single plate appearance last season carried with it the classifications of both the hitter and the pitcher. Before getting too granular, however, here is the overall fastball data for each of the three types of pitchers:

Pitcher FB% Velocity Movement

Finesse 56.4 89.92 6.60/7.96

Neutral 55.3 90.53 6.27/8.38

Power 61.3 92.36 5.87/9.21

Conventional wisdom holds true here, as the velocity and movement data trend in opposite directions. Next I wanted to find out how the different types of pitchers varied their offerings, and if their were specific off-speed pitches that each group favors:

Pitcher FB% CU% SL% CH%

Finesse 56.4 9.8 15.1 13.6

Neutral 55.3 11.9 14.1 12.1

Power 61.3 9.5 15.6 8.2

The table above can be slightly misleading since it shows the overall percentages. Lacking an electric fastball, finesse pitchers incorporate off-speed pitches more frequently, but the interesting aspect here is the actual distribution of those pitches. Power pitchers tend to throw two pitches while their finesse counterparts are more inclined to throw up to four pitches a high percentage of the time. This is largely lost in the overall percentages because it fails to differentiate between the fastball/slider and fastball/curveball power pitchers; it combines the two, which distorts the data. The percentages of off-speed pitches, outside of the changeups which greatly favor the finesse group, appear quite similar because of this lack of differentiation. In fact, it looks as if the only difference between the two types of pitchers is in their use of fastballs and changeups. In actuality, there are many more finesse pitchers that average the overall percentages above than there are power pitchers who match these numbers. At this juncture it appears that success for finesse pitchers stems from using fastballs with more movement as well as a more varied approach in dealing with opposing hitters. Staying with the fastball, let's look at how the frequency, the velocity, and the movement data shift in each pitch classification when shown in conjunction with the different types of hitters:

Pitcher Hitter FB% Velocity Movement

Finesse Contact 57.6 89.84 6.59/7.99

Finesse Average 55.9 89.81 6.57/7.92

Finesse Power 54.3 90.36 6.74/7.95

Neutral Contact 57.5 90.49 6.32/8.39

Neutral Average 55.3 90.52 6.27/8.43

Neutral Power 53.8 90.96 6.19/8.35

Power Contact 63.5 92.31 5.87/9.22

Power Average 60.4 92.29 5.89/9.20

Power Power 58.8 92.54 5.85/9.19

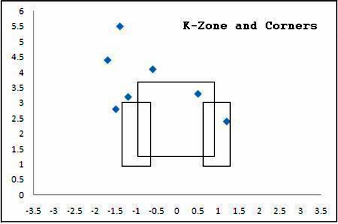

Let's focus primarily on the results against power hitters. Against hitters with clout, finesse pitchers throw their fastballs not only with some extra tail, but they also add a half-mile per hour of velocity. Without sacrificing movement they begin to throw as hard as their neutral peers. Neutral pitchers see an increase in velocity against power hitters as well, albeit with a drop-off in movement; harder but slightly straighter. Power pitchers, whose vertical movement is more telling than their horizontal, see similar results: higher velocity with less movement. All three groups show a decline in the frequency with which they use their fastball as the hitters grow more powerful. No matter the pitching classification though, power hitters see a more varied pitch distribution and harder fastballs. What about location, an aspect of pitching that is stressed from the little leagues on up to The Show? Finesse pitchers are occasionally referred to as "junkballers" due to their propensity for throwing off-speed pitches on the corners or out of the zone, attempting to coax the hitters into making mistakes. Their reputation as strategists portends precision control and a higher ability to live on the black, hitting the corners of the strike zone. Do they really throw as high a percentage of pitches on the corners as their reputations would indicate? Instead of boring you with the technicalities of how the zone corner ranges were determined, here is a diagram that shows the usual strike zone as well as the corners. Anything outside of the corners horizontally constituted an out-of-zone pitch, as did anything vertically above or below.

Plugging in the actual measurements, here are the breakdowns of pitches on the corners and pitches completely out of the zone for each of the pitcher/hitter sub-groups:

Pitcher Hitter C% OOZ%

Finesse Contact 19.1 20.8

Finesse Average 20.1 22.3

Finesse Power 19.9 23.4

Neutral Contact 18.2 21.3

Neutral Average 19.1 23.2

Neutral Power 19.6 23.8

Power Contact 18.1 21.9

Power Average 18.3 23.3

Power Power 18.4 24.7

Again, conventional wisdom holds true; finesse pitchers throw more pitches on the corners than power pitchers. The difference between the two, however, is not nearly as much as their reputations might suggest. Keep in mind that while a one or two percent difference might seem small, it's quite significant when dealing with sample sizes exceeding 80-90,000 pitches. The 1.5 percent drop-off in pitches on the corner to power hitters between the two groups equates to approximately 1,200 pitches. Power pitchers throw a higher percentage of pitches out of the zone, which might seem counterintuitive at first, but ultimately makes sense. Think of Brad Lidge, who throws a nasty slider that plummets well out of the strike zone. A pitch of that caliber provides such little time for the hitter to respond that it works extremely well by falling out of the zone. Finesse pitchers may be able to extend the strike zone due to their knack for hitting the corners, giving out-of-zone pitches the potential to result in strikes, but they cannot induce the same feeble swings on these out-of-zone offerings as power pitchers. For as long as the game has been deconstructed, the qualities that make pitchers effective have been at the forefront of analysis. Why does one pitcher succeed while the other fails if both possess similar abilities? And how do pitchers who look as if they belong in a softball league manage to stick around for so long while remaining effective? As the data in this study shows, finesse pitchers have a different approach to dealing with the various types of hitters than power pitchers do. The junk-ballers and strategists can't afford to make the same kinds of mistakes that a power pitcher is able to get away with. Despite their differences, both sets of hurlers are quite comparable in several areas, detracting from their reputations as being polar opposites. The areas in which they differ are very important, however, and should not be written off based on slight percentage discrepancies given the massive sample sizes involved. Finesse pitchers are able to succeed with seemingly mediocre talent and "stuff" because they distribute their pitches in more varied sequences, hit the corners more often, deliver their offerings with more movement, and have the ability to make adjustments depending on the tendencies of the opposing hitters.

Eric Seidman is an author of Baseball Prospectus.

|

Hey Eric - nice article. Quick question - does anyone weight the credibility of a pitcher's contribution to the sample based on their results? That is, you explicitly discuss Moyer - successful junkballer - but not Ian Kennedy - a significantly less successful finesse guy. You don't really want to treat these guys the same in an analysis, *if* you're interested in what good pitchers of a particular type do. Just a thought.

I agree there is a difference between the Moyers and Maddux's and the Kennedy's. What actually interests me more is the pitchers with reverse-numbers. As in, the guys who throw below 89 mph classified as power pitchers and above 92 classified as finesse.

I think that if I were to specifically discuss finesse pitchers I would separate them into a couple groups and determine what makes a specific finesse pitcher successful. This study was more about quantifying the differences between power and finesse.

The difference is Kennedy was never the finesse/control pitcher he was made out to be. His walk rates throughout the minors were never great - just good. The only thing he has in common with control artists like Slowey, Moyer, etc... isnt control - its marginal stuff.

Take a look at his walk rates. He walked WAY more guys than Slowey in the minors. Kennedy has been typecasted as something he's not.